Rhuddlan Castle: Conservation of Castle River Dock

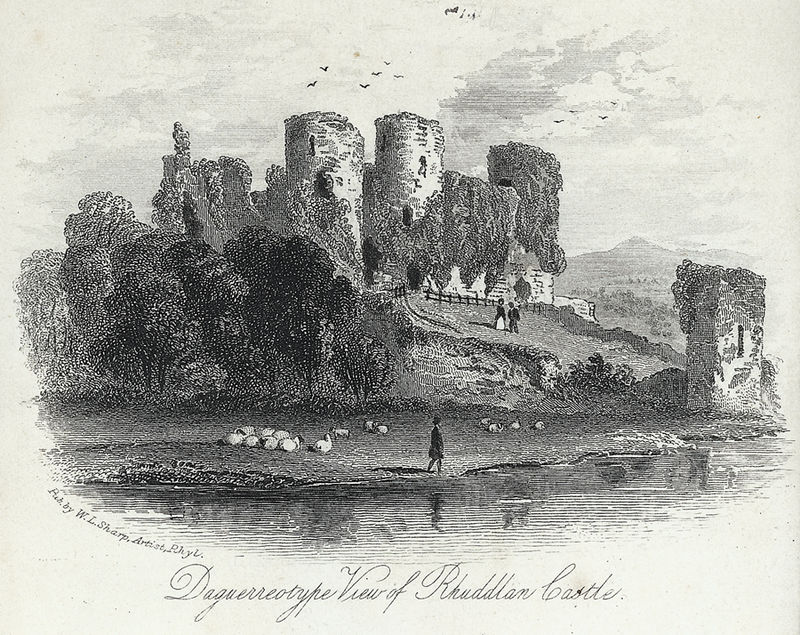

The impressive Rhuddlan Castle stands today as a dominant, yet ruinous, feature alongside a once strategic crossing point of the river Clwyd in Denbighshire, North Wales. The castle can be seen on the approach to the town, lending an enchantment to the view and awakening the imagination, of a time long past, and of the stories behind its existence. Now, Cadw and a team of skilled masons are helping to preserve this historic site for present and future generations.

The impressive Rhuddlan Castle stands today as a dominant, yet ruinous, feature alongside a once strategic crossing point of the river Clwyd in Denbighshire, North Wales. The castle can be seen on the approach to the town, lending an enchantment to the view and awakening the imagination, of a time long past, and of the stories behind its existence. Now, Cadw and a team of skilled masons are helping to preserve this historic site for present and future generations.

Rhuddlan’s story is understood to be long and significant, with a castle being present in this area since as early as the 8th century. But what remains of the monumental structure today was constructed over a much shorter period; a time when Englishmen were feverishly seeking to conquer Welsh lands, receiving much social and martial rebuff for doing so. Throughout the 12th and 13th Centuries castles were built across North Wales by Englishmen and Welshmen alike, to act as fortresses for military, political, and social domination of the areas they commanded.

Rhuddlan, one such castle, was constructed in the 13th Century in a concentric form (walls within walls), which allowed defence to be offered by the outer walls and the higher inner walls in unison. As with most ruinous castles, much of the outer walls have disappeared, however the inner walls, and the sections that once created the moat that ringed the castle can still be clearly appreciated by visitors to this day.

Rhuddlan, one such castle, was constructed in the 13th Century in a concentric form (walls within walls), which allowed defence to be offered by the outer walls and the higher inner walls in unison. As with most ruinous castles, much of the outer walls have disappeared, however the inner walls, and the sections that once created the moat that ringed the castle can still be clearly appreciated by visitors to this day.

The historic site is now one of over a hundred monuments managed by Cadw, the Welsh Government’s Historic Environment service. To provide an accessible and well-protected historic environment they manage various programs of work to the wide range of monuments under their custodianship, and at Rhuddlan their most recent conservation program is ensuring the consolidation of an extremely important area of the monumental ruins. Located to the south west of the castle, connected to the outer walls and moat structure, is the clearly discernible Gillot’s tower.

This is believed to be where access was provided from the river to the castle. When construction began, Edward I wanted the castle to have access to the sea and as such ordered the canalising of the river, creating a straighter and deeper channel for ships to have access. This extraordinary feat took three years to complete, and to this day the river continues to follow this man made course. To accommodate the ships it is thought that a water postern was created, providing one of the castle’s four access points via a dock where ships could load and unload supplies and men. The u-shaped enclosure of the dock was composed of solid masonry walls, with a rubble core, which acted as a retaining wall to earth behind. Unfortunately much of the faced stone has been lost on the side furthest from the castle, but a large amount remains on the nearest side of the enclosure, allowing visitors to clearly see the make-up of the docksides and even discern the methods of construction where the rubble core is exposed.

This is believed to be where access was provided from the river to the castle. When construction began, Edward I wanted the castle to have access to the sea and as such ordered the canalising of the river, creating a straighter and deeper channel for ships to have access. This extraordinary feat took three years to complete, and to this day the river continues to follow this man made course. To accommodate the ships it is thought that a water postern was created, providing one of the castle’s four access points via a dock where ships could load and unload supplies and men. The u-shaped enclosure of the dock was composed of solid masonry walls, with a rubble core, which acted as a retaining wall to earth behind. Unfortunately much of the faced stone has been lost on the side furthest from the castle, but a large amount remains on the nearest side of the enclosure, allowing visitors to clearly see the make-up of the docksides and even discern the methods of construction where the rubble core is exposed.

To help conserve the dock walls, a program of works was outlined by Cadw, architects from Donald Insall Associates (DIA), and then carried out by the specialist conservation firm Recclesia Ltd. The team of masons’ first task was to ensure any vegetation was sensitively removed from the stonework, asthis can cause significant bio-deterioration due to the penetration of root systems into open joints and cracks and the subsequent displacement or splitting of stones. But a lesser known reason for the removal of vegetation growth is that it can create chemical imbalances, which alter the pH of the stone surface and mortars, a common cause of stone and mortar decay.

To help conserve the dock walls, a program of works was outlined by Cadw, architects from Donald Insall Associates (DIA), and then carried out by the specialist conservation firm Recclesia Ltd. The team of masons’ first task was to ensure any vegetation was sensitively removed from the stonework, asthis can cause significant bio-deterioration due to the penetration of root systems into open joints and cracks and the subsequent displacement or splitting of stones. But a lesser known reason for the removal of vegetation growth is that it can create chemical imbalances, which alter the pH of the stone surface and mortars, a common cause of stone and mortar decay.

Once the sensitive removal of vegetation was complete, offering full access to the stonework, the team of skilled masons were able to begin the process of raking out any failed areas of pointing, cleaning away any earth deposits being forced through by water ingress from the banks behind, and repointing with new lime mortar. Lime mortar is used as it is known to be generally softer and more porous than stonework, allowing it to act in a protective way, as it tends to decay in preference to the stone. The use of cementitious mortars for these types of work had been prevalent in conservation from the later 19th Century through to the 1970s, but is fortunately accepted today to be very damaging to stonework, as it tends to be nonporous and of a different chemical make-up.

Moreover, lime mortars allow masons to be in full control of the choice of materials for the mixture and the method of application, guaranteeing it to be the most suitable for its environment. This process undoubtedly allows a more sensitive and sustainable approach, and has the added benefit that the high skill level required not only guarantees a high qualityof workmanship but is alsomore reflective of the skill and craftsmen originally employed during the castle’s construction.

Moreover, lime mortars allow masons to be in full control of the choice of materials for the mixture and the method of application, guaranteeing it to be the most suitable for its environment. This process undoubtedly allows a more sensitive and sustainable approach, and has the added benefit that the high skill level required not only guarantees a high qualityof workmanship but is alsomore reflective of the skill and craftsmen originally employed during the castle’s construction.

Due to the exposed position and the nature of weather, water was pooling on exposed surfaces and entering the structure through cracks and open joints, accelerating the decay of this unique section of the castle. To combat this, areas of the remaining facing stones and exposed rubblework required extensive localised pointing.

Other areas also required flaunching, a method that would reduce the opportunity of water ingress and pooling on the stonework by channelling the water off the stone. Both flaunching and pointing should be done with extreme care and consideration as, if applied too liberally, they can significantly change and even obscure a visitor’s understanding and interpretation of a site and therefore be harmful to the heritage significance. At Rhuddlan there was extensive collaboration between CADW, DIA, and Recclesia’s masons which helped to prevent damaging both the evidential and aesthetic value of the site, whilst confirming an approach that would be both financially viable and provide suitable protection of the dock enclosure walls.

Other areas also required flaunching, a method that would reduce the opportunity of water ingress and pooling on the stonework by channelling the water off the stone. Both flaunching and pointing should be done with extreme care and consideration as, if applied too liberally, they can significantly change and even obscure a visitor’s understanding and interpretation of a site and therefore be harmful to the heritage significance. At Rhuddlan there was extensive collaboration between CADW, DIA, and Recclesia’s masons which helped to prevent damaging both the evidential and aesthetic value of the site, whilst confirming an approach that would be both financially viable and provide suitable protection of the dock enclosure walls.

If you would like to find out more about Rhuddlan and when it will be open later this year then visit the website: cadw.gov.wales/daysout/rhuddlancastle. For any technical advice in relation to conservation of built heritage then please feel free to call 01244 906 002 and one of Recclesia’s team will be happy to help.

For further exciting projects from Recclesia visit www.recclesia.com